Bob Carver: Rebel Audiophile

Ask Bob Carver why he’s something of a controversial figure in audio and he sounds almost apologetic. In the mid-1980s, Carver challenged some pretty high-end audio magazines to show him an amplifier, any amplifier, and he’d develop one that sounded just as good but cost less.

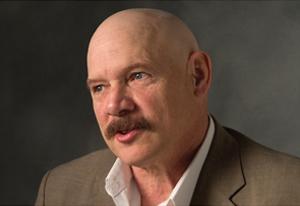

Bob Carver, founder of Carver Corp., Phase Linear, and Sunfire

“>

Bob Carver, founder of Carver Corp., Phase Linear, and Sunfire

ASK BOB CARVER WHY HE’S SOMETHING of a controversial figure in audio and he sounds almost apologetic. In the mid-1980s, Carver challenged some pretty high-end audio magazines to show him an amplifier, any amplifier, and he’d develop one that sounded just as good but cost less. And he did.

“But I’d challenged a belief system: A $20,000 amplifier doesn’t necessarily sound better than a $500 amplifier,” Carver says today. “Now that I’m older and wiser, I realize I was too full of myself. I should have said, ‘I can make my $500 amplifier sound pretty close to your $20,000 amplifier.’ Then people would have listened and said for themselves, ‘Wow, I can hardly tell them apart.’”

In the ensuing years, Carver founded three companies: Carver Corp., Phase Linear, and now Sunfire, makers of high-end audio products. The holder of 27 patents spoke to PRO AV lovingly about audio from his lab in Seattle.

PRO AV: How would you describe your life’s work?

BOB CARVER: My passion has been music and the science of reproducing music. My goal has been to build a sound stage in front of me with audio equipment so that I can close my eyes and really feel that I’m in the presence of a live orchestra. That’s been my guide from the beginning.

PRO AV: And where did you see the need for audio innovation to help realize your goals?

BC: Back in, say, the late ’70s, when we listened to stereos before four-channel and Dolby came along, the presentation was basically a flat curtain of sound strung between two speakers. Perspective had not yet come into audio. I wanted to put science to all of that and understand how we heard what we heard. From that came something I called Sonic Holography. The patents have long since run out, but the technology is used today and called virtual surround. It has the ability to take sound from two speakers and place that sound stage deeper than the speakers, in front of the speakers, to the left of the speakers, to the right of the speakers, higher than the speakers, and make it much more believable.

PRO AV: Where could we see your work in pro AV applications?

BC: I made high-powered professional amplifiers for several pro AV applications, like taking sound outdoors in stadium settings. I called them magnetic-field amplifiers. I made one a long time ago that weighed 11 pounds and put out over 1,000 watts. Very high power made the lives of sound engineers easier. It gave them freedom and power they didn’t have before.

At one point, my Phase 700 amplifier found its way into many professional AV applications. They were typically used for outdoor venues, but they also found their way indoor. They were used here at the Seattle Opera House, before it was rebuilt with modern acoustics, to augment existing acoustics and make the opera house sound much better. They’d have a live performance and you could not tell there were amplifiers to enhance the sound.

PRO AV: Pro installers are beginning to face requirements from clients to use energy-efficient, green solutions (see “Greening Lessons,” January 2008, page 16). How does some of your technology address those concerns?

BC: Our amplifiers typically run very cool when they’re idle. And our power amplifiers don’t even get hot when they deliver a lot of power. They have what I call a Tracking Downconverter power supply, which is so efficient the amplifier stays cool without any heat sinks. The tracking is only a few volts, as opposed to hundreds of volts.

Typically, the current that goes to a speaker has to first drop across, say, 100 volts, and if it’s 5 amps to drive the speaker, the 5 amps drop across 100 volts and that’s 500 watts of wasted heat, with maybe only 100 watts going to the speaker. That power has to come out of the wall and be generated by a power station, which runs on fossil fuel. So it’s wasteful.

A Tracking Downconverter tracks the audio at 6 volts, not 100 volts or 80. So when those same 5 amps drops across 6 volts, it’s only 30 watts instead of 500 going up in heat. And the same current goes into the loudspeaker, so the speaker gets its 100 watts.

PRO AV: Could digital amplifiers solve the same problems as a Tracking Downconverter?

BC: Digital amplifiers have held promise for years. Every year I think they’re going to appear and render the Tracking Downcoverter not obsolete but competitive. But they haven’t been able to deliver, mostly because they blow up too often, or they’re underpow-ered, or they just don’t sound very good. They blow up because they’re switching transistors on and off, and it’s hard to have them switch trillions of times in a lifetime and not, sooner or later, by accident or through a control glitch, switch on at the same time, which is curtains for the amplifier. But they’re getting better every year and verging on the promise of being lightweight, highly efficient, and great sounding.

PRO AV: Where will future improvements lead us?

BC: Improvements will be divergent, but I’ll talk about my favorite. Right now, using the best stereo or multichannel playback, if we close our eyes even a 12-year-old can tell he or she is listening to a system and not a live event. But it’s getting better. The push is going to be for sound that’s even more realistic. There’s going to be science in microphones, in playback equipment, in speakers and amplifiers, and there will be an enormous amount of scientific work into how we hear what we hear; how our brain works with our ears to give us the illusion of a world out there.