You’re looking at the electronics for a single channel of an Ampex 351 tape machine that was built in the early 1950s. Ampex manufactured console, rack and “portable” versions of this machine, as well as the model 350, all with a choice of full-track, half-track, or stereo 2-track heads. The 350 and 351 used the same transport, available in versions that ran at tape speeds of either 3¾ and 7.5, or 7.5 and 15 ips (that’s Inches Per Second for all you young ‘uns).

The 350 and 351 appear almost identical; the only way to tell them apart from the front panel is by the little black dot that appears underneath the Input Transfer Switch on the 351 (see photo). The 350 does not have the black dot. A look around the backside reveals that the 350 is a very different animal, employing 12SJ7 preamp tubes, while the 351 uses 12AX7 and 12AT7 tubes in the audio path. More importantly, the 350 requires a separate power supply, whereas the 351 has the power supply built into the electronics module.

The 350 and 351 each have a rear-panel XLR that can accept microphone- or line-level input, and this is where things get interesting (in those days, it was not uncommon for a tape machine to have a microphone input).

Rewind

About two years ago I was visiting my friend and Audio Yoda Tony Ungaro, an outstanding engineer and composer. As I was ready to leave, he said, “Wait, I have something for you…” Tony brought out this Ampex 351 and said, “It’s a channel from an old tape machine. It has a mic input that you can use for a preamp. Play around with it—you’ll figure it out.” Oh yeah.

Off I went on my merry way, already having decided that, even if this thing doesn’t produce any sound,1 it’s going to live in my rack because it looks awesome. At this point I knew nothing about either the Ampex 350 or 351, so I thought a good start would be to see if it powered up. Brilliant. Lucky for me, this one was a 351 with the built-in power supply. The rear panel had some kinda’ funky power connector that I figured I’d never be able to find.

When it comes to trying new gear (or new old gear), I have no patience, so I hacked apart a spare IEC power cable, tack-soldered it to the funky power connector, put on a pair of safety glasses, made the sign of the cross and flipped the power switch. The light for the VU meter illuminated, and I held my breath as the tubes started to glow. I had a fire extinguisher nearby—just in case. Holy Fire Bottles Batman, it worked! And nothing exploded.

I continued to hold my breath while I thought of what to do next. Well, the thing has a mic input and a headphone jack (mono, of course), so I dug out a ’57 and a pair of cans, plugged them in and turned some knobs. Lo and behold, the 351 passed audio, and had plenty of gain, so it could indeed be used as a microphone preamp.

Not being one to tempt the fate of the Audio Gods, I thought it would be a smart idea to make sure I could safely plug the 351 into an AC outlet while evaluating its operational condition. I started snooping around the dark corners of the web where us audio geeks hide out when trolling for old gear. I learned that the power connector is a Hubbell 7466, and it mates with a Hubbell 7464V. Twelve bucks later I had a Hubbell 7464V connector, and easily made a new power cable from that IEC cable I hacked apart. I could have removed the old Hubbell receptacle and replaced it with an IEC inlet, but I wasn’t going to start cutting into the chassis.

I next did a quick test run in the studio, connecting an RCA 44BX to the 351 and recording the results. Not too shabby. The Ampex 351 (and the 350) has ridiculous amounts of gain, like on the order of 90 dB—so I could easily use it with a low-output ribbon mic to record the sound of a mouse eating cheddar cheese at 100 yards.

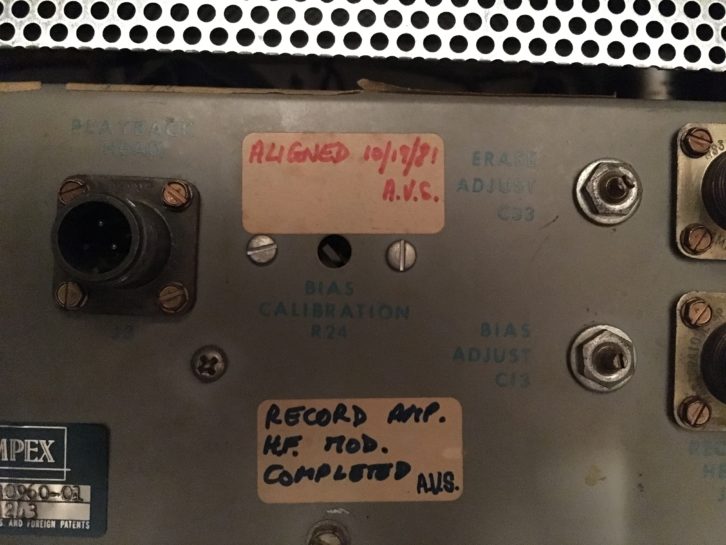

I left the unit powered on for an hour or two (supervised, of course) to see if it was reasonably stable while I read the handwritten notes that were scribed on masking tape on the rear panel: “Aligned 10/18/81.” “Record HF Mod Completed A.V.S.” “Tubes Checked 5/12/78.” Wow. I wasn’t even an audio pup back then. I love stuff like this.

Knowing that the 351 was operationa,l I began the journey of refurbishing this Beautiful Beast and learned quite a bit in the process. I’ll discuss some of the highlights over the coming months.

An interesting tidbit of audio history is the influence of Bing Crosby on the development of Ampex. In the late 1940s, prior to the use of recording tape, Crosby had to perform his radio show live twice: once for the East Coast audience and a second time for the West Coast audience. When Crosby heard the sound quality of the Ampex 200A tape recorder, it became apparent that he could record the show and use the taped performance for the West Coast broadcast instead of having to perform the show a second time. Crosby’s Philco Radio Time was the first ever delayed radio broadcast. Crosby subsequently placed an order for twenty Ampex model 200A recorders at a cost of $4,000 per machine (about $42,000 each in 2019 dollars), with a deposit of more than half—thus changing the course of audio and broadcast history.